Put a Plan in Place

Spray Foam Magazine – Spring 2022 – The mantra for spray foam professionals is to Spray it Tight and Ventilate Right! This means ventilating three different ways, and each is vitally important to the success and profit of your job, and each comes with some cost. The most important point regarding cost is it’s far more expensive to not ventilate than to ventilate properly.

Before the spray foam gun trigger is pulled on a job there must be a ventilation plan in place. The plan must include:

- Ventilation while the foam is being sprayed

- Ventilation shortly thereafter

- Ventilation forever thereafter

1 – Ventilating the workspace while the foam is sprayed should be well known to every spray foam contractor. An exhaust air blower and a supply air blower are positioned on opposite sides of the application area, to remove vapors and odors during the spray process. If this step is skipped the work zone can be unhealthy, the odors saturate the structure, and Step-2 below takes much longer to complete.

2 – Ventilation should remain in place after the foam is sprayed. How long should it be left running? As long as it takes to remove all odors. For most foam products this is a matter of hours or a couple of days at the most, but there are some foams with longer residual odors, so the blowers need to remain in place until the odor is gone. If this step is skipped, the homeowner will likely be upset, and it can be extremely expensive to correct. Homeowners have demanded removal of all foam sprayed in the house due to lingering odors. Skipping this step can crush profit.

3 – Ventilation forever thereafter is not necessarily the job of the SPF contractor, but it’s imperative that the SPF contractor arranges for whole-house ventilation in every home he or she air-seals and insulates with spray foam. Our product is just too good at sealing the skin of the building to leave the house without a mechanical air exchange system. The code requires mechanical ventilation of tight homes, but far too often the HVAC contractor doesn’t understand the requirement, or it’s not done effectively.

Here’s the problem with the residential ventilation code and the ASHRAE 62.2 ventilation standard cited in many state and local codes. If we apply the required continuous ventilation rate, we exhaust so much air that we just paid to heat and cool, the house is no longer energy efficient.... unless we recover some of the energy from the air we’re exchanging.

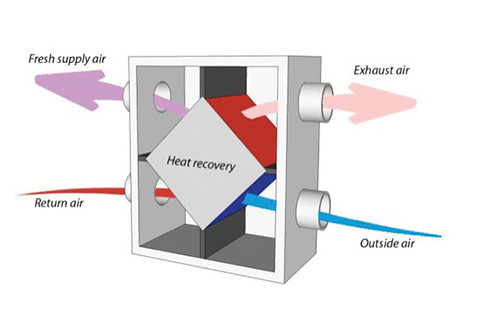

Simplified diagram of air-to-air heat exchangers

Putting this in perspective:

An average house in the U.S. these days is 2400 square feet and let’s say it has a 9’ average ceiling. The volume is 21,600 cubic feet. ASHRAE 62.2 says we need to ventilate at a rate of 50 CFM continuously.

50cfm x 60 minutes per hour x 24 hours per day x 365 days per year = 26,280,000 cubic feet of air per year! The Empire State Building’s volume is 37 million cubic feet, so our code says we need to heat or cool the equivalent of the Empire State Building every 16 months just for ventilation!

So, how can we get adequate ventilation and save energy? With a Heat Recovery Ventilator (HRV) or in some climates an Energy Recovery Ventilator (ERV).

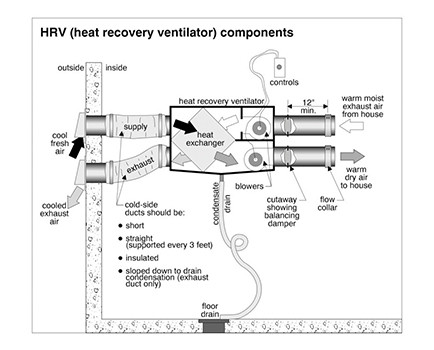

An HRV or ERV system consists of two air ducts: one that brings outside air in and one that exhausts air from the indoors out. Both incoming and outgoing air pass through a heat exchanger, a device that allows heat to transfer from one airstream to the other without the two airstreams mixing. These heat exchangers are usually aluminum, plastic or plasticized paper with high thermal conductivity.

HRV’s are favored in the north because the moisture in the air is not exchanged from the exhaust air to the make-up or incoming air and HRVs are thought to be less likely to freeze in the winter.

An ERV has a highly vapor permeable heat exchanger that allows exchange of both heat and humidity. This can be helpful when the outdoor air is either much higher or much lower RH than the indoor air being exhausted. Let’s say it’s 85°F and 80% RH outside and 75°F at 50% RH inside. We pay to run our air conditioner to reduce the inside temperature and humidity so it’s beneficial for the exhausted air to absorb moisture and heat from the incoming air then send it back outside. This way the air conditioner doesn’t have to run as long to control the temperature and humidity.

HRV and ERV systems comprise more than just the energy exchange core they’re known for, and a significant factor in analyzing cost effectiveness of these systems is the fan power needed to move the air across the heat exchange core and through the ductwork. In some areas where energy cost is high and the climate is mild, these units don’t save money even though they do save energy. The cost to run the blower motor(s) is greater than the cost of the energy they recover. Heat exchange systems also require maintenance to operate efficiently.

Most HRVs and ERVs are 65% - 80% efficient at transferring the heat from one air stream to the other. One brand touts an 88% efficiency but at a significantly higher purchase price than others on the market. This higher cost unit also uses half the energy to run than some of its competitors.

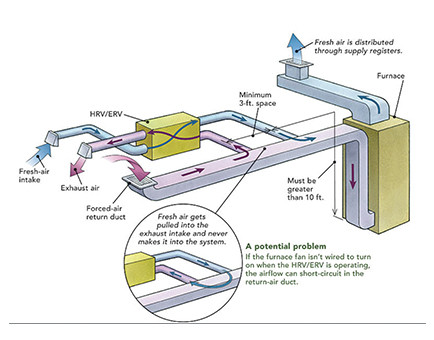

The best way to install an air-to-air heat exchange system is to duct the supply air from the unit to each room in the house. This is known as a “distributed system,” and it provides fresh air to the whole house. Combine this with a high efficiency air filter and you have the best IAQ possible. This system is in addition to your heating and cooling system since it needs to run continuously in order to exchange the air in the house adequately while running only the small blowers in the unit to move the air.

A compromise used by many HVAC installers is to duct the air-to-air heat exchanger through the central HVAC system. The problem is the frequency the central AC fan needs to run to properly heat or cool the house. In mild weather with a well-sealed and insulated house, the HVAC system might not come on for days at a time, but the ventilation would need to run more often so the strategy is to turn-on the furnace or air handler fan to distribute the ventilation air. The motors in most central systems are large and use far more energy than the heat exchanger motors so these combined systems are often not cost effective.

Conventional thinking over the past 30 years of HRV and ERV use has been to use ERVs only in predominantly cooling climates where the outside temperature and humidity are higher than indoors. The Cold Climate Housing Research Center in Fairbanks recently conducted a study of ERVs in sub-arctic climates and found them highly effective and less subject to freezing than HRVs. They attribute this to the rapid exchange of water vapor before the dew point is reached in the heat exchange core. When it’s extremely cold outside, there is very little water vapor in the air so slightly humidifying the incoming air can be helpful.

Conclusion: Air-to-Air heat exchangers work. They can save energy and make a home more comfortable depending on the climate. They can save money by pre-conditioning the air needed to replace the stale air exhausted from the home by the code-required ventilation system. The best HRV or ERV systems are ducted to most or all rooms in a house and are designed with a high efficiency air filter. HRVs and ERVs can pay for themselves through energy savings with the greatest return on investment in Zones 1 & 2 with ERVs and Zones 6 and higher with HRVs.

The spray foam contractor should never pull the trigger on a spray foam job until there’s a three-part ventilation plan in place. It’s usually up to the HVAC contractor to design and install the whole-house ventilation system, but remember, if he doesn’t install an efficient and effective system, you could be blamed for either poor energy savings or a stuffy, stinky house, just because you did a fabulous job air-sealing and insulating with spray foam. It’s your responsibility on every job to make sure there’s a three-part ventilation plan in place before a drop of foam is sprayed.

Direct any questions you have about statements made in this article to Mac Sheldon: 503-650-9833 // mac@sheldonconsulting.com

*Spray Foam Magazine does not take editorial positions on promotional or sponsored; individual contributions to the magazine express the opinions of discrete authors unless explicitly labeled or otherwise stated. The inclusion of a particular piece in the magazine does not mean that individual staff members or editors concur with the editorial positions represented therein.