Igniting Change

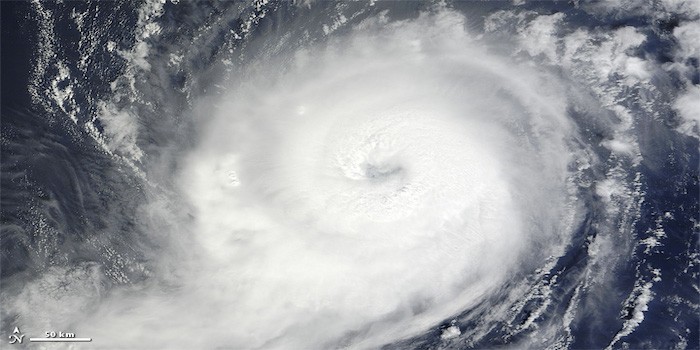

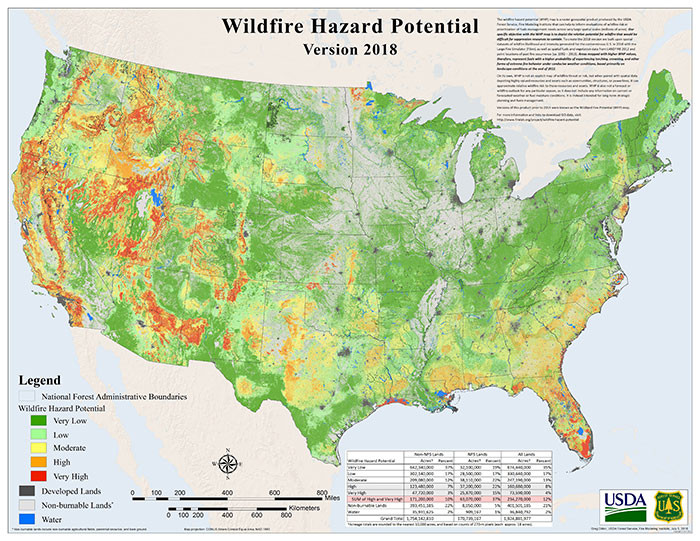

SPRING 2019 – Turn on the news in late summer and you’ll likely hear about wildfires threatening or consuming houses in fire-prone areas of the country, or what are called Wildland-Urban Interface Zones. News coverage of such fires often shows charred remains of homes in developed neighborhoods, not necessarily built amongst the trees where the fires start. It is also common for homes several blocks away from forest fires to catch fire. Fortunately, spray polyurethane foam (SPF) may be able to help to protect homes from catching fire.

Many houses located a great distance from the fire line ignite during forest canopy fires. These fires occur when the tops of trees catch fire, intensely burning needles bark and limbs. The burning embers, or firebrands, can travel several blocks due to the immense heat from the inferno. If firebrands land under a deck, in a pile of debris next to a house, or are drawn into an attic through an attic vent, they can start a fire. But with the right information and building materials, these house fires are often preventable.

There are several commonsense fire prevention practices for homes built near forests, grasslands, and agricultural fields—including keeping combustible debris away from the house and from under decks. And, if you live in a Wildfire-Urban Interface Zone, there’s more you can do to stay safe. Eliminating attic vents prevents embers from entering the eave, roof or ridge vents and starting a fire in the attic.

The Federal Government recognizes the threat of wildfires to federal buildings, which prompted an Executive Order in 2016. The Wildland-Urban Interface (WUI) Federal Risk Mitigation Executive Order 13728 (EO) released on May 18, 2016 aims to mitigate wildfire risks to Federal buildings located in the WUI, reduce risks to people and help minimize property loss to wildfire. In 2015 alone, more than 10 million acres of wildlands burned, requiring the service of more than 27,000 firefighters and resulting in $2.1 billion spent by the U.S. Forest Service (USFS) and the Department of the Interior (DOI) to suppress the fires—a record amount. Over the last decade, the fire season has become two and a half months longer, and fires covering more than 10,000 acres increased, with the average area burned by wildland fires doubling in the last three decades to an estimated seven million acres per year. As climate change impacts, and in particular, drought conditions, become more commonplace, the risk due to wildfire is expected to increase.

Over 46 million homes in 70,000 communities are at risk of Wildland Urban Interface (WUI) fires, which have destroyed an average of 3,000 structures annually over the last decade. WUI fires are a rapidly growing threat with an annual loss of over $14 billion. Within the last 100 years in the U.S., six of the top 10 most damaging single fire events involving structures were WUI fires and the WUI is continuing to grow at approximately 2 million acres per year. According to the USFS, 32 percent of housing units in the United States and one-tenth of all land with housing are situated in the WUI. Protection of public and private property in the WUI is also the largest cost driver for both Federal and State wildfire suppression operations.

Wildfires can spread rapidly through forest canopy fires, when the tops of trees catch fire, intensely burning needles bark and limbs, which then send burning embers or firebrands traveling through the air–potentially landing under a deck, in a pile of debris, or into an attic vent.

Not all states have adopted the International Wildland-Urban Interface Code (IWUIC), but those with the highest wildfire potential have and spraying foam in unvented attics can help to comply with the code. The IWUIC spells out construction requirements for three levels of protection. In medium to severe wildfire threat areas, eave vents are not allowed and if roof vents are used, they are restricted to size and location such that it’s difficult to get adequate attic ventilation. Using an unvented attic assembly is the easiest and safest way to comply with the code. The International Residential and Building Codes both have provisions for unvented attics based on a decade of peer-reviewed research. When constructed according to code, unvented attics can be built in any climate zone and have substantial energy advantages over vented attic construction, and unvented attics have no openings for firebrands to enter.

Spray polyurethane foam is widely used to insulate and air-seal unvented attics where duct systems are located above the ceiling. SPF is sprayed to the underside of the unvented roof deck, preventing firebrands from entering the attic. In addition to fire prevention, SPF offers unparalleled air-sealing for energy efficiency. This not only benefits the environment, but also leads to real homeowner savings. SPF eliminates energy-wasting air leaks and lowers electricity bills. In fact, if all 113 million single family homes in the United States used SPF, Americans could save up to $33 billion in energy costs each year.

Fire prevention from firebrands is a significant threat to homes near wildfire-prone forests, grasslands and agricultural fields. Insulating unvented attics with spray foam is cost-effective, code compliant, energy-efficient and a viable solution to keeping homes and buildings safer during fire season.

Using an ICC-ES, Appendix-X rated foam enhances fire safety from the inside as well as the outside. Ignition barrier spray foam assemblies are required by the code in unvented attics and they are intended to slow the involvement of foam in a fire. Appendix-X rated foams are designed and installed so they are difficult to ignite and burn slowly if they do catch fire. The best combination for fire safety is to eliminate attic and crawlspace vents and use a slow-burning, true Appendix-X rated foam like SucraSeal® from SES Foam. Installing non-Appendix-X tested, fast-burning foam and relying on oxygen depletion to protect service workers in the attic is a dangerous shortcut that could come back to haunt a spray foam contractor should there be a tragic attic fire.